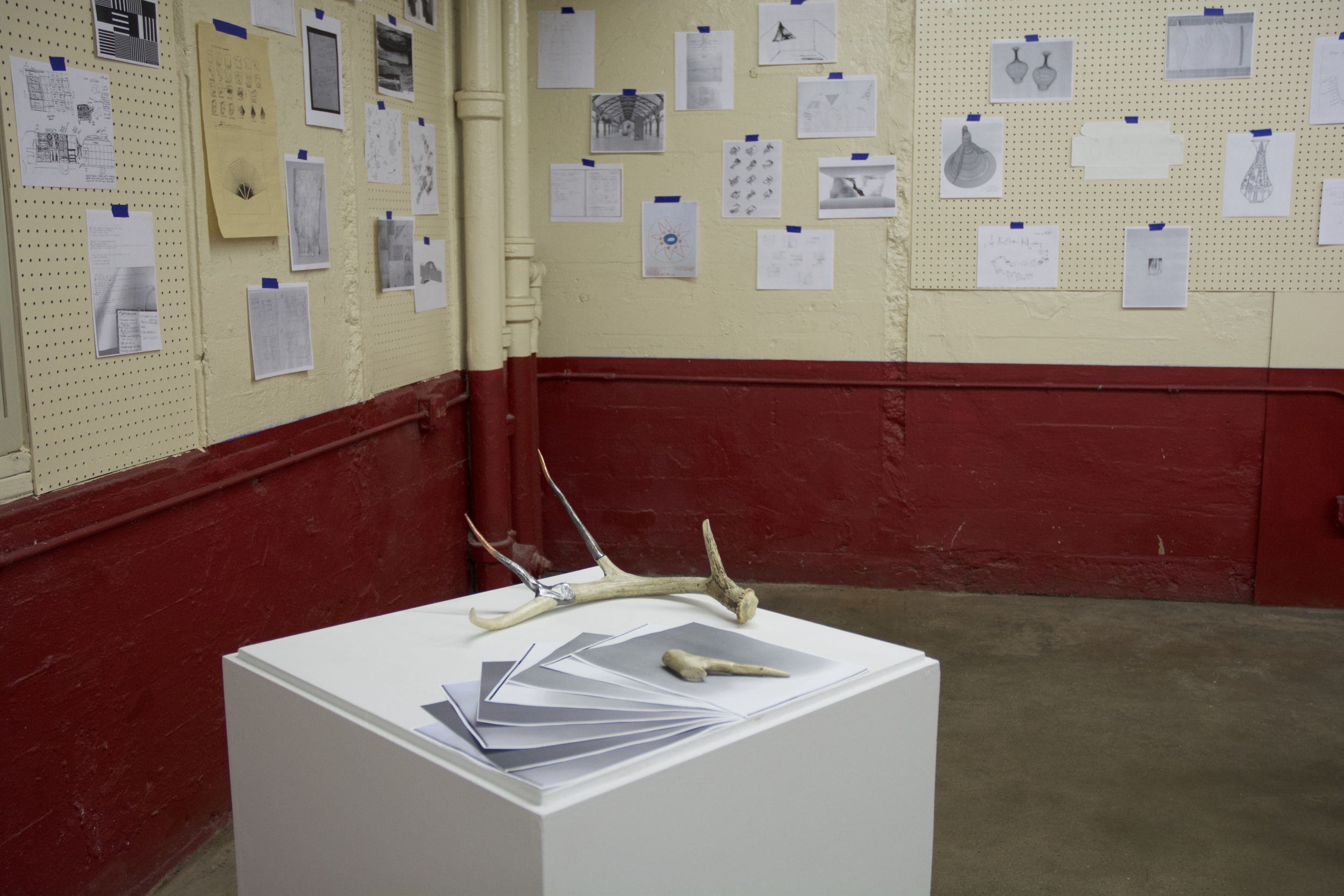

Nathan Abhalter Smith: How have you come to be working in metal? Have you been doing it for a long time, and has it been a long route to here?

Brian Blankstein: Well, the route to here is long and twisting.

NAS: Yeah, perfect.

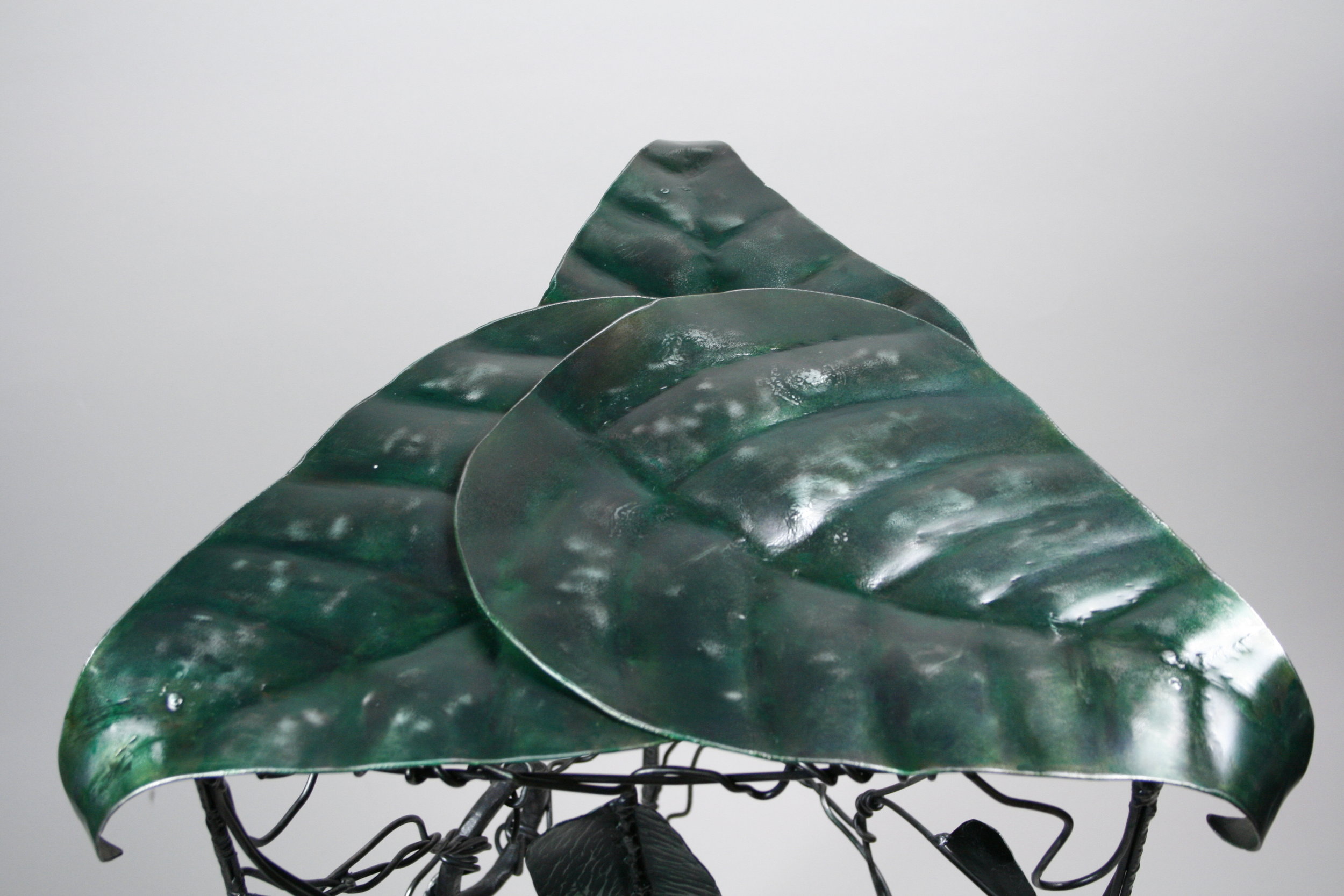

Coffee Table (detail) by Brian Blankstein

BB: As a kid, I was the kid that was always playing with Legos and building stuff. Didn’t really figure out that I could build stuff as an adult until I was 25 or 26. I went to school – I did math and computers and stuff like that – I hated it and didn’t really realize why. I started building stuff with my hands, at that point mostly woodworking, and started taking woodworking classes, and I was really really into it, and I realized this is what I had been missing all this time. So I was at Chicago School of Woodworking sort of right after they opened. They didn’t have any classes then, so I quickly exhausted their catalogue. I was in the middle of a career change, and had three or four months off, so I did a kind of unofficial apprenticeship thing with them, so I like hung around and did chores and stuff for them and used free shop time. One of the things that I built when I was there was I built this table that had like an etched, inlaid glass top. So I was figuring out that I really liked working with a lot of different materials, mixing things together. A pretty obvious next step for me was, I want to learn how to do stuff with metal.

NAS: So that you could change the composition that much more. . . .

BB: Yeah. And metal and wood are beautiful together.

NAS: Yeah.

BB: And I was totally into steampunk at that point – so I was like, if I do stuff with brass and wood, that going to be amazing.

NAS: Yeah, yeah. (Laughing) Have you disavowed steampunk?

BB: No, I just . . . that was my entry point to a bigger world. And I still love that aesthetic, but I don’t know if the steampunk lifestyle is for me.

NAS: (Laughing) Sure.

Trivets by Brian Blankstein

BB: So at that point I’m like, how do I learn how to do stuff with metal? Because wood was fairly straightforward to me, but no one in my family makes stuff, I didn’t have a lot of friends who made stuff or anything like that, so I didn’t have a good sense of what was involved in the metal world. I know there are people who weld stuff together and make crazy sculptures and stuff, but I don’t know what the hobbyist entry point is. . . . So I started looking at welding programs and stuff like that at community colleges, but it was all very geared toward you’re going to be a certified welder welding girders together, and like fixing submarines and stuff like that. And I was like, that sounds like I could get some technical knowledge, but it wouldn’t be very fun.

NAS: Yeah. Yeah, I assume there’s rigor, and weld this weld over and over and over to X, Y, Z. . . .

BB: Yeah – don’t smile. Well, I don’t remember how, but I eventually found the Evanston Arts Center. And I looked up the departments and I went to a class and Matt [Runfola] taught me how to weld, and it was awesome, there was so much stuff here. And I’ve kind of been, on and off due to availability of time, I’ve been pretty enamored of metalwork for the past . . . five-ish years or so? So I still do a little bit of woodworking, but most of what I’m doing is in metal. And the transition from only working in wood to metal was really weird because like, in woodworking, you’re always checking things to make sure they are perfect and they’re right. In woodworking, you’re working with organic materials, but it itself is not a very organic process. You have to plan everything in advance, and if you cut something too short, you’re done. There’s not really a good way to recover from that most of the time. And so, I’m in the metal shop for a few weeks, and I’ll buy some rod stock, and I’m like checking it for straightness – and everyone is looking at me like I’m crazy, and I realize – oh, if this isn’t straight, I can just bend it, no problem. And you’re working stuff and something falls off – okay, just stick it back on. I don’t like this this way, how about over here? And you can just improvise and you don’t have to plan ahead. You can do pieces where you’re planning everything ahead, but there are pieces where you could improvise. I made a table that was all this ropey viney leafing, and there was no real plan. I didn’t know anything except, it’s triangular, it’s going to be about this tall . . . go. It was a really freeing experience because I could just play, and not have to have everything planned, or check the plan.

NAS: Doing the table with inlaid glass – thorough plan, you have to follow everything, or it’s a total disaster. . . .

BB: There was a little bit of improvising, because I realized I wanted it to be something else, and I couldn’t do it, so I was like okay, I’m going to do this thing . . . but, yeah, you had to plan that in advance. So I really liked the freedom of metal, and I love the feel of it, and the weight of it is nice, and I did a lot of things with some metal and some wood combined, and that was a lot of fun. I was mostly doing welding early on, and at some point I discovered forging. And I was like, I love all this other stuff, but this really speaks to me. And I don’t know what about it. . . . It’s very physical. And you can really feel the metal as it moves. I don’t know, I really enjoyed it, and the process of how you get things from point A to point B, I think made a lot more sense to me. It’s not like it’s a complete replacement for any of this other stuff – I still weld things together, but forging is just fun.

NAS: The physical aspects seem particularly pronounced. Is it changing your thought process about the thing you’re doing because you have to be so physical with it?

BB: I don’t know that it changes my thought process so much as, my thought process didn’t work quite as well in other media.

NAS: Yeah, yeah. Okay.

BB: Not that any of them were completely alien or anything, I’m pretty good at figuring that kind of thing out, but this just felt very natural. And after years of doing things where I’m sitting at a desk all day, to be up and swinging a hammer for hours and hours, it’s exhausting and it’s great.

NAS: Nice. Do you have a desk job now?

BB: I have no job now. For the last five years of so, I was a mechanical engineer in product development. We were doing a lot of prototyping and making little test pieces, and stuff like that, and that part I loved, I loved: okay, we need to cobble a thing together. It can look like anything you want, but it really has to feel like this . . . we want to test this thing out. That was really cool. But then there was a lot of sitting at a desk doing CAD, or filling out forms, and things like that, and I was like, this part’s not for me. As that went up and the prototyping went down, I was like, eh. Okay, I’m done.

NAS: Was there a particular project or thing you were making when you started working with the forge where that’s when it clicked, or was it even just the fundamentals, the entry point which sort of immediately made it obvious that this was the thing for you?

BB: I know I talked to Matt [when CIADC opened], and I know that at that point I was already specifically interested in forging. I did a little of it back at Evanston Art Center, but there was maybe a year or two where I wasn’t able to get up there, I was just too busy. I already had my mind on forging, and I don’t remember how I got to that point. Other than maybe it was just that I had done enough of it that it was like, I miss this. I want to weld, but I really want to forge. It might have been that I had the idea I wanted to learn how to forge a knife, to make really nice kitchen knives, or something like that.

NAS: Have you done that?

BB: I’m working toward it, I’ve made several knives just out of scrap metal, but to make a really good knife you need to use high carbon steel, because that allows you to harden it, a knife won’t hold an edge unless you harden it, so just like the tip will fold over. That involves some more complex processes; you have to do heat treating and tempering and stuff like that. So I’m learning a bit about that, how to make them sharp enough, but I’ve gone through the process of getting the rough shape out. It’s something I’d still like to do at some point, it’s sort of always in the background, when I have a spare moment and I’m not sure what else to do, I’ll go ahead and make another rough knife now.

Firepokers (detail) by Brian Blankstein

NAS: You were saying the other day that you have hundreds of firepokers?

BB: I was imagining having hundreds of firepokers. I have more like a dozen.

NAS: Okay, well, speculative hundreds of firepokers – were they going to be straight up ornamental, or. . . ?

BB: So, I knew that I didn’t know a lot about forging. And it seemed like the best way to learn would be through repetition, and a firepoker seemed like a kind of thing that is fairly simple, straightforward, but allows for enough variety to experiment with different techniques. It’s a quick project, so it’s not like I’m spending weeks and weeks on it, I can get through one in a day or two. Probably a lot faster once I’ve done a few, a quick turnaround to generate a lot, which is helpful for learning.

NAS: So at a dozen, you were like, alright, I’ve gotten what I can get out of this?

BB: I’m going to go back to them at some point, but I have firepokers piling up in my apartment, I don’t have a big apartment, and I don’t have a fireplace.

NAS: (Laughter)

Firepokers on table by Brian Blankstein

BB: So, I’ve given a couple of them away. A lot of the things I’ve made historically have been out of need. Like, I need a table. I’m going to go make one. Something to hang things on a wall, I’m going to make that. So, something else came up and I was like, oh, I should actually go do the things that are important, rather than more firepokers. But it was good, but making the firepokers I got to learn techniques, such as making handles that look and feel good, things with a good hold.

NAS: Are they like the handle that’s on that wrench [in the exhibit Country, Life & Economics, which was recently in the CIADC exhibit space]?

BB: That was something that I had made to put on a firepoker, but I never made the poker to go with it, and we needed a handle, so I was like okay, I’ll just stick a nice handle on this thing. You know, if I need to make another one, I’ll make another one.

NAS: Nice.

Twist Wrench by Brian Blankstein and Emily McCormick

BB: And I have an idea for the Demo exhibit, but I don’t have time to do it. Here’s my idea – and if someone wants to use it, they can. I would make like a dozen different handles, and get a ball, and weld them all to the ball sticking out at different angles. If I had time, that’s what I would do for that. And if someone else has time to steal my idea, that would be fine.

NAS: It’s sort of like a mace head full of handles, or. . . .

BB: Or like a big jack.

NAS: Right.

BB: That’s what I would do for Demo. I might still do that sometime because I feel like it would be fun.